Building habit-forming apps: 4 cognitive biases you need to know (Part 2)

Following up on last week’s Part 1, we’re diving deeper into how cognitive biases shape user behavior in app development.

This time, we’re unpacking Labour Illusion, Curiosity Gap, Scarcity, and Loss Aversion—with real-world examples from Hinge, Tinder, Duolingo, ASOS, and more.

Discover how these biases influence engagement, retention, and monetization—and where ethical boundaries come into play.👇

Labour illusion

Definition

Labour illusion is when apps make processes appear longer or more effort-intensive than they need to be, enhancing users’ perception of value.

Example

I strongly suspect that Hinge, a dating app, makes you feel like it’s handpicking your best match by artificially increasing load times when a user is landing on the app or is updating their filters.

Similarly, food delivery apps shows the break down of the process involved in delivering your dish straight to your bed — sorry, table.

There’s a step-by-step update of the process (“Finding the best driver,” “Your driver is on their way,” “Your food is being prepared,” and in some cases, there’s even an animation of the food being cooked!). Technically, some of these steps, such as the matching, are quicker than the animations suggest.

This approach doesn’t aim to make you feel guilty about the delivery person struggling on their bike while you eat pasta in bed.

Instead, it makes users feel more informed and involved in the process, increasing their patience and satisfaction with the service. Additionally, it can create a sense of transparency and trust, as users see (or believe they see) the effort being made for them.

Curiosity gap

Definition

The curiosity gap intrigues users by providing just enough information to pique their interest but not enough to satisfy it immediately.

Example

This technique can boost engagement and retention as users seek to discover more content. Dating apps such as Tinder blur the profiles of people who have liked you, requiring you to subscribe to see who they are.

Headspace, a meditation app, tempts users with intriguing content; if anyone has done the “Miraculous Migration of Salmon” meditation, please contact me — I really want to know!

Instagram launched Threads a few months ago and added snippets of tempting content to encourage users to create an account on Threads and leave X.

Finally, Duolingo has a clear learning path filled with unknowns and future achievements, harnessing the curiosity gap to motivate users to continue their learning journey. The anticipation of uncovering new knowledge or achieving the next level keeps users engaged and encourages daily app usage.

Scarcity

Definition

Finally, my favourite bias, scarcity, makes people place higher value on items or experiences perceived as rare or limited.

Example

E-commerce websites like ASOS use limited-time offers and flash sales to encourage frequent visits. Bumble makes their subscription feel really premium and exclusive by adding “VIP invite”.

This principle can be applied in various ways to boost app engagement and monetisation.

Loss aversion

Definition:

People tend to avoid losses more than they seek equivalent gains. We hate losing or letting go of what we have, even if more could be gained. Prospect theory states that a loss hurts more than an equal gain feels good. In other words, losing $1,000 “hurts” more than the joy of gaining $1,000.

Example:

Many education and fitness/well-being apps leverage loss aversion to help users form habits with a mechanism called “streaks”. Put simply, streaks are a consecutive series of actions or activities performed without interruption, representing a commitment in pursuing a particular goal or habit over time. This makes streaks a robust repetition mechanism.

Streaks can motivate users by creating two feelings: a sense of ongoing accomplishment (“I have a 100-day streak!”), and a sense of increasing loss aversion (“I need to use the app today or I’ll lose my streak!”).

The most famous example is Duolingo, the leanguage learning app, but many other education and wellness apps also employ this strategy for habit building.

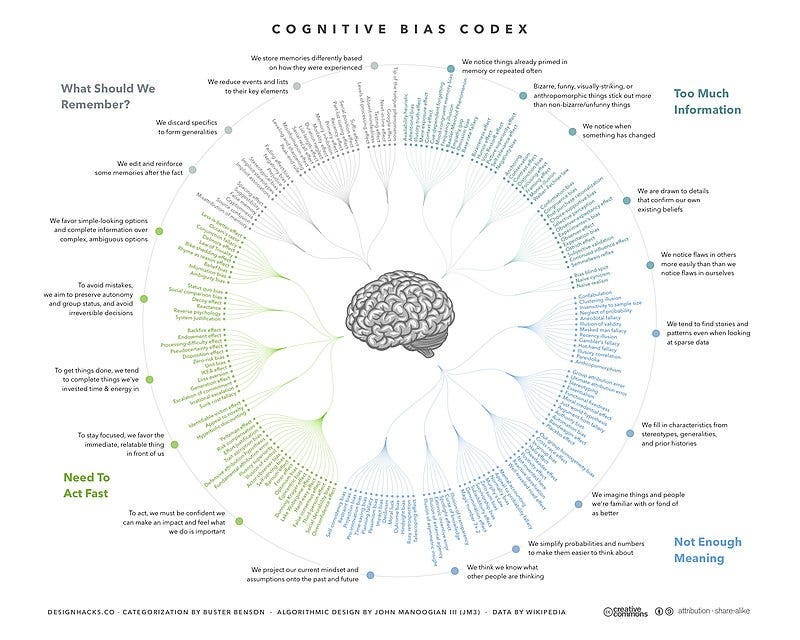

We have seen some common cognitive biases and design principles and their usage in popular apps but there are many more. You can refer to this illustration to explore more of them.

Ethical considerations

Being able to change someone’s behaviour is quite a great power, and with great power comes great responsibility.

Here are a few ethical considerations to keep in mind:

Transparency: Users should be aware of how and why their data is being used and should be able to make informed choices.

User Autonomy: While nudging can be a powerful tool for positive behaviour change, it’s crucial to respect user autonomy. This means providing options without manipulation, allowing users to make choices that are genuinely in their best interest, rather than solely serving the app’s metrics.

Long-term impact on users: Consider the long-term effects of engagement strategies on user well-being. Are you encouraging addictive behaviours? Does the app promote meaningful engagement or just surface-level interactions? It’s essential to weigh short-term gains against potential long-term consequences for users’ mental and emotional health.

Inclusivity and Fairness: Cognitive biases don’t affect all users in the same way. What works for one demographic might not work for another, and in some cases, could even be harmful. It’s important to consider diverse user experiences and ensure that your app’s engagement strategies are inclusive and fair to all users.

Wider strategy

To be effective, cognitive biases and design principles must be used as part of a larger strategy. Wise uses this framework as their own Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. If you vaguely remember your philosophy class, the short summary is that you have basic needs such as food, water, and shelter at the bottom of the pyramid, with more philosophical questions at the top. In short, there’s no point in talking philosophy and Plato to someone who is starving.

Similarly, there’s no point in applying tactics to a product that doesn’t solve a real customer problem or provide a reliable service. For Wise, the issue was sending money abroad. They solved it by making the process simple, convenient, and even fun.

Cognitive biases and design principles belong to the top of the pyramid, they can be used to make an experience delightful but don’t make up a strategy.

In conclusion

- There are many cognitive biases and design principles to explore.

- Ethical considerations are crucial.

- They can complement, not replace, a solid strategy.

What cognitive bias and design principles can you implement in your app?

Another interesting article, Angele!

Do you see these cognitive biases as mutually exclusive, or does a certain concept work well alongside another?

These concepts are really interesting and sound useful to also apply in a non-app environment. Last-minute sales campaigns and similar things come to mind.